2025 Awardees: Nancy L. Oyler Student Award in Counseling

Congratulations to the five Counseling students who received this scholarship award that supports and encourages graduate-level training and clinical excellence in rehabilitation counseling.

Read More

Beyond Graduation: Pitt Occupational Therapy Capstone Projects Create Ongoing Impact

Several recent projects have continued to evolve and grow well past the students’ graduation—shaping clinical practice, community engagement and quality improvement initiatives.

Read More

5 Reasons for PAs to Choose Pitt DMSc

The DMSc was created by PAs for PAs, with the busy schedule of practicing clinicians in mind. It’s designed to enhance your current place of practice, expand career opportunities and fit seamlessly into your personal and professional life.

Read More

Advancing Occupational Therapy Education Through Clinical Simulation at Pitt

The simulation provides students with realistic, interactive experiences that mirror the complexities of real-world clinical practice within a safe, structured environment.

Read More

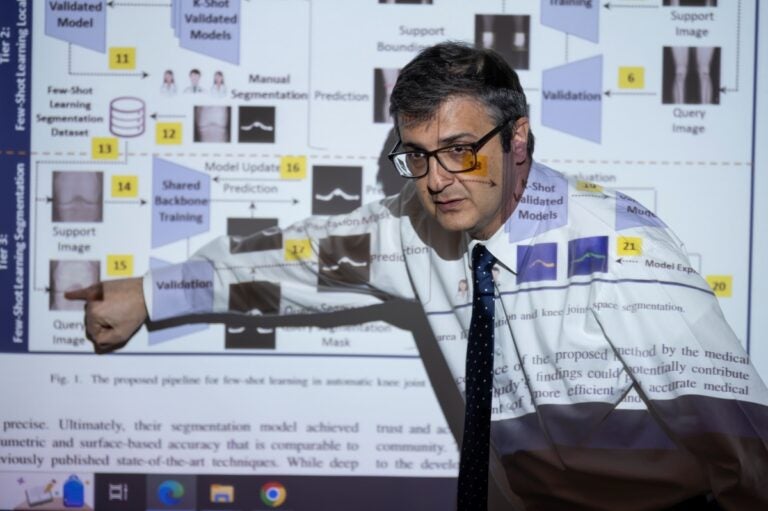

Equipping Practitioners with the AI Tools of the Future

Professor Dipu Patel has developed the country’s first and only digital health course for students in the school’s Doctor of Medical Science program, helping students gain an understanding of the benefits and challenges of various digital health technologies and their impact on patient care and clinical practice

Read More